Riding for the plot

The idea was to trace out the full run of whichever River Avon was geographically nearest to me. I could find three River Avons or Avon Waters in Scotland – one which opens into the Clyde at Hamilton, another in the Cairngorms, and one near Falkirk. The nearest one to me here in Glasgow was do-able in a day’s cycle, and it had the happy benefit of re-tracing some of the steps – wheel revolutions? – I’d taken in previous years, while adding another layer to my familiarity with this area of the Scottish countryside. Why was I doing this? The idea came from a combination of two things: firstly, a kind of sentimentality about where I grew up (near the River Avon in Bristol), and secondly, a kind of homage to the psychogeographists. I’d read my Iain Sinclair and Rob McFarlane, Rebecca Solnit on walking, Edward Thomas’s In Pursuit of Spring, and, most importantly, Jon Day’s book on cycling: Cyclogeography. I’d read these and wanted to give my rides an impetus and rationale beyond the sporting. Cycling is, to me anyway, as much an intellectual pursuit as a physical one – the figuring out of the bicycle’s mechanics, the planning of routes, the gauging of weather, time, and distance, the schooling it offers in reading a landscape. All of this is going on before and after the ride, as well as while you’re turning the pedals. “Cycling” isn’t just the business of being on the road, it’s all the stuff around it too.

All of this is to say that the ride was a bit contrived, but that needn’t mean it was false or superficial. Most rides are, one way or another, contrived: you decide a distance you want to go, what sort of landscape you want to see or what towns you want to visit, and you plot a course that meets those requirements. Plotting. Yes. That’s a crucial part of it. It’s a good word, plotting. Peter Brooks makes a lot of it in his book Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. He writes about Sherlock Holmes stories – about detective stories more generally – as ones where that connection between storytelling and the exploration of place found in the word “plotting” is made most clear: Holmes solves his cases by re-treading the steps of the criminal, simultaneously plotting out movements and motives. I wonder if this sense of plotting is what the historian Graham Robb has in mind when he writes at the beginning of The Debateable Land about “those two inseparable pursuits: writing and cycling.”

My ride along the length of the Avon Water, then, was a plot. It was invented, it was planned on a map, and it was vaguely intended as a kind of story. Quite what the story was, though, I wasn’t sure. I was aware, though, that I was already shaping it far in advance of actually setting out. I was, truth be told, forcing the issue a bit. Sinclair and McFarlane are much better at disguising their own contrivances; their writing makes their exploration seem somehow fated. But once you get out on your bike, you forget all of that. It just becomes a day out on the bike. It’s like reading a really good novel; you forget that it’s all a made-up story. On a really good bike ride, you have the same desire to find out what comes next.

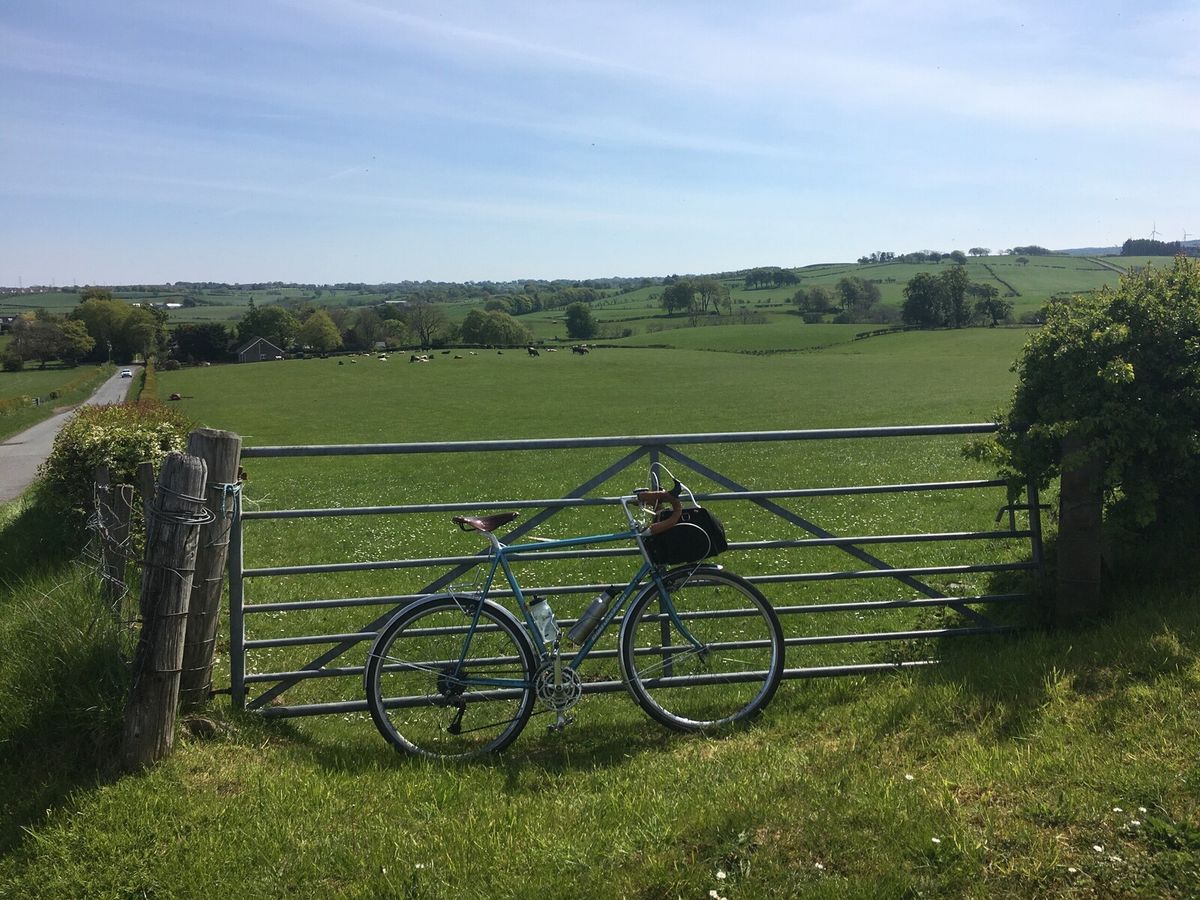

Glasgow spreads widely, much wider now than it needs to be; a taxi driver once told me that the city has far too many taxis than it really requires, because a disproportionate number of laid-off shipbuilders ended up driving them. And the population of the city in the days of the empire was much larger than it is now. Glasgow is a baggy city, with lots of empty space. That said, it’s only four miles or so from Crosshill, where I live, to the countryside that begins just past Clarkston. Once you’re in the countryside, though, especially past the surprisingly – though not unpleasantly – twee Eaglesham, you’re in a landscape of tree-lined lanes dotted with dairy farms. The lanes are well-maintained so the milk lorries can collect their loads, which is a boon for cyclists.

The fifty-mile ride actually involves twenty-five before you reach the source of the Avon Water, in the moorland south of the A roadthat goes from Kilmarnock to Strathaven. It’s this part of the ride that is familiar to me; it’s one of my favourites. Those lanes from Eaglesham up over the Ardochrig road that runs over the end of the ridge that becomes Eaglesham Moor, which houses Whitelee Windfarm, the UK’s largest on-shore farm, are wonderful: narrow, more often than not dappled, and, in spring, bordered by cacophonous hedgerows. The climb up to the car park where dog-walkers and mountain-bikers park is long enough to allow you to imagine it’s a key part of one of cycling’s spring classics, those gruelling races held in the Belgian and northern French countryside in March and April each year. The view from the top is a peach: looking back the way you’ve come, you see Glasgow laid out for you, and if it’s clear, the Campsies behind it and Ben Lomond and other mountains behind them.

The problem with the twenty-five mile pre-amble is that you risk getting tired before the ‘actual’ ride has started. That happened the first time I attempted it. Basically, I learned that the plotted route didn’t work. The aim of the ride was not to do it as quickly as possible, for speed and fitness. This route was for discovery, and discovery almost inevitably involves some ambling and frequent stops. But if you have to cycle twenty-five bumpy miles to reach the allotted area for discovery, you’re less likely to be in the mood for discovery once you actually get there. So, first revision: flip the route – take the train to Hamilton and start at the Avon’s mouth into the Clyde, and ride ‘up’ it, to its source. But then what? The problem with the area between Kilmarnock and Strathaven is one faced by many areas of the British countryside: it used to have a railway line but doesn’t anymore. The Darvel and Strathaven Railway, as it was called, closed to passengers in 1939. Railways are cyclists’ friends because you can (usually) take a bike on a train; railways provide easy bail-out routes for tired pedallers. What this meant for this ride is that once you’ve cycled to the source of the Avon Water, it’s up to you to get home from it. In this case, that either involves cycling back the way you’ve come and getting the train home from Hamilton, or cycling those twenty-five bumpy miles that used to be the pre-amble to the ride when it was the other way around. Either way, you’re still riding another twenty-five miles. This is the problem with plots; they only go one way, and once you’re in the middle of one, you can’t easily extricate yourself from it.

This conundrum came at the end of summer 2019, and soon the clocks changed and the ride became unviable until spring came around again. This is the second act lull, the bit of the story where events slow down. This is another problem with plots: they need to keep moving. Which is also true of cyclists. I decided, then, that the only way to actually do this ride was to become a reader rather than a writer; that is to say, to not try to construct the ending to the story and instead to see what happens when the time comes. In practical terms, this meant getting the train to Hamilton, riding to the source of the Avon, and then just figuring it out from there.

But then the pandemic happened. This, at least initially, curtailed any real possibility of getting the train to Hamilton. If, previously, the route was threatened by its own awkwardness, now it was threatened at a more fundamental level – the very concept of cycling outside was one suddenly subject to a range of public health announcements.

And then, on one of the first rides after lockdown had been relaxed a little in 2020, with my friend John, we happened upon the Avon Water. I recognised it by a process of deduction: our ride so far that glorious summer’s day was a ghost of my original plot, but I hadn’t realised it. Stories are about context, too: if you think you’re in a detective story you might not notice the domestic drama playing out in front of you. Because I hadn’t set out that morning with the rationale of doing my Avon Water ride, I hadn’t read that landscape we’d been cycling through in the same way. That I wasn’t alone, and me and John chatted as we rode, added to the distinctive feel of riding what should have been familiar roads. So it was with quite an exclamation that I registered my dawning realisation that we were riding alongside the Avon Water, and that the little stone bridge we’d just gone over had been built over it, and that we weren’t that far from the source.

I would absolutely be lying if I said that realising where we were led to some kind of epiphany, or that finally finding the Avon Water enabled some sort of deeper connection with my childhood. This is perhaps not surprising – the ride was always a contrivance. The reason for it was never actually that connection, which was always a spurious concept; the reason for the ride was the ride. That story was a rationale for riding where I did, not why.Plotting a ride is always, underneath everything else, a way of making sense of something that is overwhelming – the sheer basic existence of space. It spreads as far as the eye can see and then some more, and you obviously can’t ride through all of it. Decisions have to be made. Some places have to be left out so that others can be included. Cyclists can’t ride everywhere at once. What needs to happen is discernment, carving out, this thing not that thing. In this case, this thing turned out to be a-really-awkward-ride-that-doesn’t-quite-work-until-you-do-it-accidentally-without-realising.

Words and pictures - Mark West

Instagram - @zingfisher